by Gloria Chiarini

by Gloria ChiariniSpecial effects for Turandot

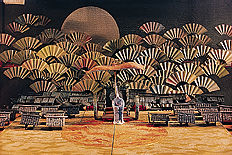

The Maggio Musicale Fiorentino is celebrating its sixtieth year of life with refined exuberance. This year's programme boasts three really wonderful operas, Wagner's "Parsifal" (for the inauguration on May 3rd), Puccini's "Turandot" and "Arianna a Nasso" by Strauss (directed by Jonathan Miller, with Zubin Mehta conducting the orchestra, as for the "Turandot"). The choreography for Haendel's ballet "Apollo and Daphne" is by Karole Armitage, while famous musicians like Mehta, Sinopoli, Sawallisch, Shipway, Jurowski and Tamayo will be conducting a series of concerts. The festival will conclude with music and ballet in Piazza della Signoria and even a performance in the Boboli Gardens, the true "stage of the Princes", and an essential part of the May Festival since the 1950's. The Uffizi Gallery will also be making its contribution towards the cultural life of the Festival by opening an exhibition dedicated to "Felice Casorati, scenographer" and his stage designs. However it looks rather as though the world of film, the so-called seventh art, will be the innovating feature of this now mature Festival. The scenery and costumes for the "Apollo and Daphne" ballet are in fact by the American film director James Ivory, the sensitive transposor of Forster's novels on the screen, though the real event in the 60th Festival hails from the Far East. Zhang Yimou, the highly praised Chinese film director of "Hong Gaoliang" (Red Grain) and "Dahong Denglong" (Red Lanterns), will be coming to the May Festival to direct Puccini's "Turandot"; first staged at the Scala on April 25th 1926, this opera was the composer's last work and left unfinished on his death. As this is the first time that a Chinese has ever directed an Italian opera, "Turandot" seems to have almost been made to measure. Simoni e Adami's libretto, taken from a 18th century theatrical fairy tale by Carlo Gozzi (the unfortunate rival of Goldoni), is set in a timeless and imaginary China and opera directors of the Western world have invariably made a jumbled use of settings, furnishings and costumes from a variety of epochs and regions of this enormous country: this mixture has often appeared rather odd to the real Chinese. Zhang Yimou's direction promises to be far more accurate and uniform, because it will be based on the true cultural traditions of his nation and the choice of a clearly defined historical period. The story is about the Tartar prince Calaf and his love for the daughter of the Emperor of China, Princess Turandot, who has such a heart of ice for (like the Phoenix) she has no qualms about having her suitors put to death if they are unable to solve her three riddles. Sunshades, pagodas, glittering dragons, splendid lanterns and costumes create a classic background to this opera composed of three acts, five scenes and about ten scene changes. A throne that appears and disappears on stage, a curving 30 metre dragon that slithers down to the ground from above and a sun that rises from beneath the stage are just a few of its components. The ordinary spectator can only have a vague idea how complicated it is to organize and direct a similar mise-en-scène from behind the scenes and make sure that, evening after evening, everything runs on oiled wheels. First the scenery, costumes and props have to be designed and carried out; then, once the curtain is up, the various lighting effects must be carefully controlled and the machinery and fly lines that move all the scenic elements across the stage must be regulated, in order to be quite certain that each piece enters at the right time and in the right place. The drop-curtain of the ministers Ping, Pang and Pong alone is formed of eight independent panels that travel along four tracks. And naturally everything must be done quickly and in utter silence. The "maestro" in charge of all this and responsible for the perfect staging of each performance is Raffaele Del Savio, director of the Scenery department at the Teatro Comunale for many years and designer of many splendid sets. He has to oversee the Theatre's fifty or more highly skilled stagehands and property men, who move with faultless ease across the stage among the mobile platforms, panels, trapdoors and "trucks", moved by hand or motor on special tracks. One of the greatest problems involved in making a performance a success is to ensure that the various platforms carrying the "pieces" of scenery come together without finding obstacles in their path and in perfect silence. The stage is slightly inclined towards the orchestra pit and it would be fatal if one of the pieces of scenery got out of control ("But it's never happened - Professor Del Savio laughingly reassures us - though problems crop up all the time"). "Turandot" is a complex opera, even though the use of technical material is half that of other performances: "Italian operas however, are never over difficult, they work in the traditional fashion" says Del Savio looking back on the far more complicated problems that were involved with some of Ronconi's stagings or the "Mephistophele", produced in 1989, which was composed of as many as 12 scenes. However the "Turandot" has taken at least 4 months to prepare, compared with a normal staging which requires on average about 45 days. The scenery contains many special effects, most of them obtained by using a "mechanized platform". Almost half the stage (which measures 27 metres by 27) is in fact taken up by a platform (12 mt. wide by 8,5 mt.), divided into five sections; two trapdoors, both 4 metres in size, are situated beneath it. This area of the stage will be used to create various scenic changes as well as a few elements of "surprise", such as apparitions and disappearances.

Costume design for Turandot |

II of Turandot |

Web

development Mega Review Srl - © 2005